Something I love about humans is the fact that we contain so many contradictions. Like someone who says they’re a vegetarian but eats bacon. People who are contradictory are some I feel the most tender toward, caught in the universal push-pull of feelings vs. behaviors. It’s a fine line between contradicting yourself and being a hypocrite, but where I’ve mostly netted out is that hypocrites are dishonest about their contradictions. They don’t see the inconsistencies, whereas a contradictor knows they’re doing something not aligned with their identity.

I am certainly a person of many contradictions, but one I haven’t been able to make sense of yet is how I love humans and think they’re so cute and yet I also hate people a lot of the time and often feel like humanity is fucked, beyond total repair. I loved a lot about Margo’s Got Money Troubles, but mostly this line from the main character, an OnlyFans pioneer, “Every day, I’m like, The world is complex and wondrous, everything is so nuanced, and then I turn on the computer, and it’s like, ‘Look at my dick!’”

And there are really any number of things that have made me feel similar to Margo in the last few years, specifically: The lady on a highway in Arkansas who threw her jumbo styrofoam cup out the window of her car onto the grass highway divider, neon red liquid splashing across the green grass. Hit-and-runs like the person who hit a couple on a motorbike outside my best friend’s house in New Zealand. I can still hear the girl’s yelping as we ran outside. All the times I walk in a crosswalk while cars inch forward, never coming to a complete stop and getting mad at you for looking at them. The man I crossed paths with in Duane Reade on my first day living in New York who told me he hoped I fucking died. And that’s not even mentioning the cable news pundits.

Shortly before the 2016 election, Barack Obama wrote in Wired that now is the greatest time to be alive and the world is better than it was 50 years ago. At its worst, the essay reads as propaganda; at its best, it’s been written by Pollyanna, if Pollyanna managed to be the first female POTUS. (And actually, it turns out whether people think the world is better today than 50 years ago depends on the current economy.)

If the world is, in fact, the best it’s ever been according to Barack Obama, then where does that leave us? Common sense says it’s inevitable that suffering exists in the world, that people will be unwilling participants in a genocide, that they’ll be starved and bombed and raped and pillaged, that we just have to accept that we live in a world where some are privileged so greatly so as to never worry about these things—in fact to just toss them aside like they don’t matter because it doesn’t impact their day-to-day reality—whereas some will face unbearable tragedies and be told to be grateful to be alive at all.

But is that the world we live in? Is that an answer we have to accept? It is, certainly, a reality. But what if it didn’t have to be? Where does that leave us, if we want things to be better but if the world is designed this way? I ask sincerely. I want the answers, and I fear we’ll never get them.

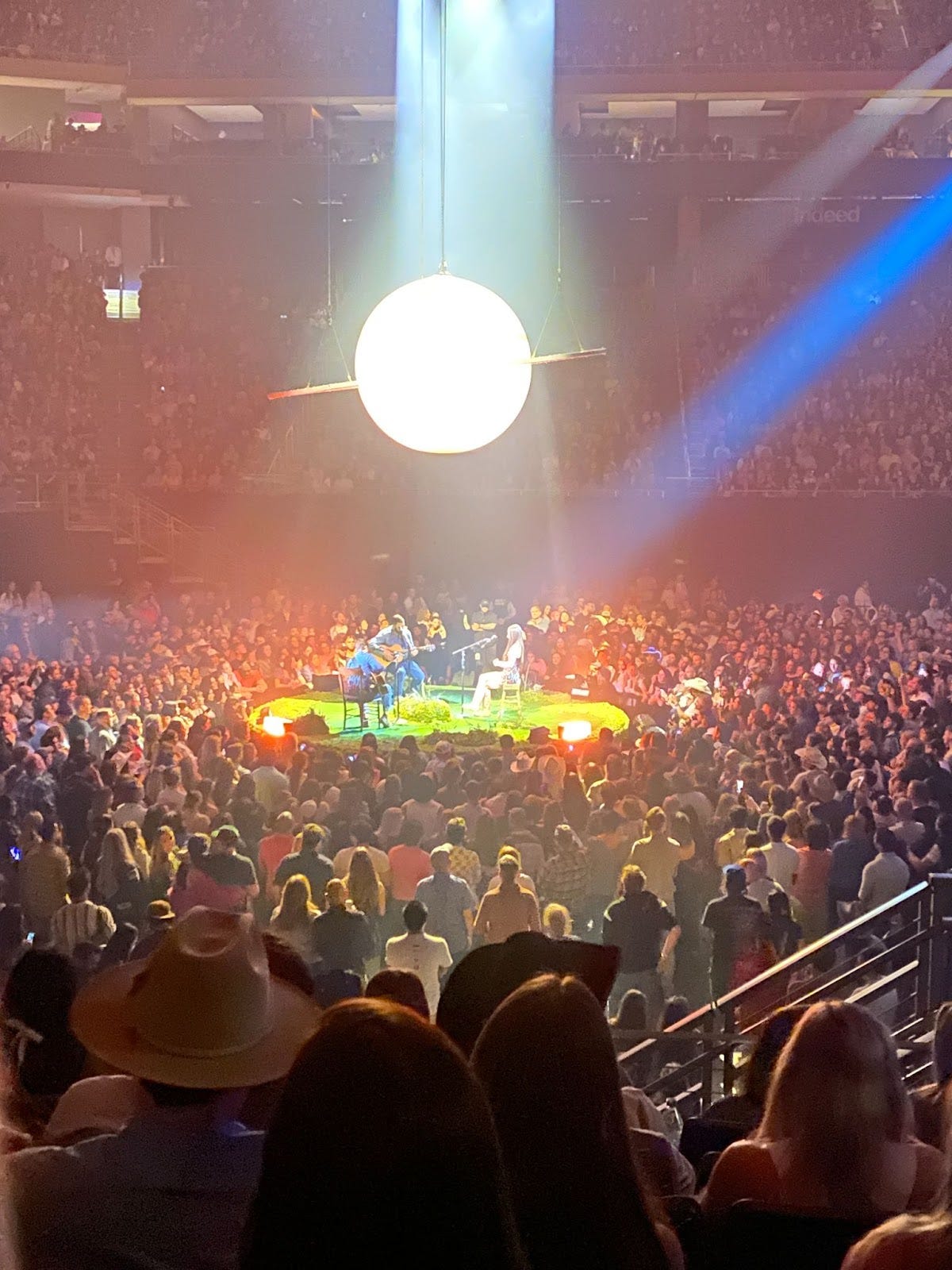

For whatever it’s worth, lately I’m taking comfort in knowing I’m not alone in this despair. Before someone tried to snatch Kacey Musgraves’ hair in Tampa, I saw her play to a sold-out venue in Austin. Beneath a warm, softly glowing Saturn, Kacey sat amongst moss and talked about writing a song after a school shooting in Nashville. In the lyrics she asks, “Does it happen by chance? Is it all happenstance? Do we have any say in this mess? Is there an architect?”

It’s an unassuming song that I breezed past when Deeper Well came out this March but has now brought on a whole new meaning after being placed into its context, as I grapple with the same questions. It’s a far cry from a previous anthem on Golden Hour, where Kacey marvels at the world with its Northern lights, psychedelic plants, bioluminescence in the ocean and muses how she doesn’t want to leave all the magic this world offers.

At first glance, the songs feel like opposite ends of the spectrum, confronting the best and worst of the world. But now I feel like they’re simply two sides of the same coin, two things that can’t exist without the other, this darkness and light, this amazement and hopelessness.

When I sat in a yoga shala in Bali in 2019, ostensibly to train as a yoga teacher but really to put off returning to the US, we talked about how light can't exist without dark. We—30 women, mostly white, privileged enough to spend thousands of dollars for a one month experience—debated if that means that good can't exist without evil to frame it, if that means that evil is inherently built into the human experience. And by association, if it means that innocent people are always going to suffer while some are so fortunate to live lives of gilded luxury. We didn’t come to a satisfying conclusion on the topic, so many questions swirling around us.

What’s clear is that people have always suffered. There have always been serfs and peasants and slaves. There have always been people fighting in the Colosseum, both literally and figuratively, tearing one another apart for sport. Hell, people used to be boiled alive as punishment. Maybe, as others have pointed out, we're just more aware of the suffering than ever before — there are soldiers making TikToks in war zones after all. Or maybe we’ve finally reached our collective breaking points.

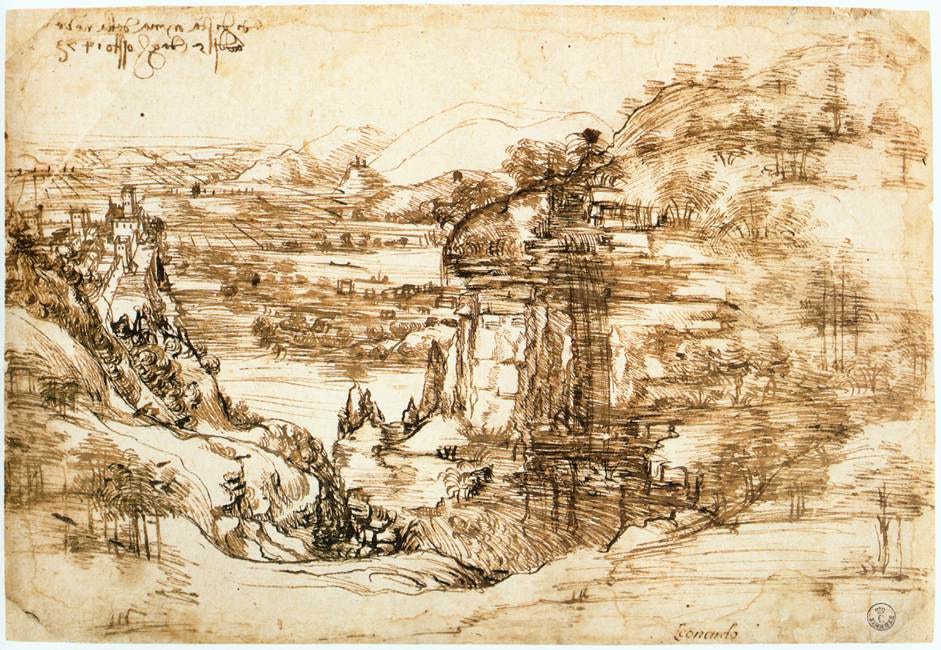

In fits and spurts over the last few weeks, I’ve been watching the new Ken Burns documentary on Leonardo da Vinci. Da Vinci is, himself, a fascinating study in contradictions. He designed military weapons but was staunchly anti-military. He was the first person in Western art to draw a landscape, he dissected cadavers to understand musculature and paint more realistically, yet he only finished around 20 paintings in his lifetime. He died feeling like a failure for having completed so little, but he’s remembered as one of the finest thinking minds in all of recorded history.

What I’ve been most struck by is his total despair at the state of humanity. He wrote in his journal, “Truly man is the king of beasts, for his brutality exceeds them. We live by the death of others. We are burial places.” If da Vinci, in the late 1400s, felt much the same distress as I feel today, then what hope is there? In some way, I could feel better for abiding this great human tradition. I could feel more connected to others across space and time. And while there’s some narrow relief in this, there’s also an overwhelming sadness that some-500 years later, we find ourselves still repeating these same patterns of cruelty.

So much of da Vinci has endured in our collective consciousness: his journals, The Last Supper, the Vitruvian Man, the freaking Mona Lisa. But I think it’s this revelation, this example of his humanity and agony, that will stick with me above all else.

I work hard to remember the good in an effort to combat the despondency: The time my Amtrak was stuck behind a train that derailed in a sinkhole and a lady from Long Island shared her cherries with me when I was hungry and made sure I got a taxi okay once we got to Penn Station. All of the people who stopped to help a woman who broke her leg when her heel got stuck in a street grate. The time I was walking down rue de Sèvres in Paris and a bunch of us were showered in rose petals from a fifth floor apartment window and everyone shrieked in delight and looked at each other and laughed, like did that really just happen? Bursting into tears at the total eclipse with 5,000 other people and then crying again seeing a similar image at a concert later that same year.

Too much of anything is a bad thing, or so they say. I’ve never found a limit to hugs or laughter or watching my dog eat peas (you really must see it). But even water, the very lifeforce that sustains us, carves canyons in the desert and swallows entire cities whole. Maybe that’s how to think about humanity too—great in small doses, catastrophic in large. Something that’s so beautiful as a whole because individual humans can be so wildly disappointing.

When you find these bright spots of people who can help one another out and show love so easily, who do the right thing on pure instinct, they feel special because other interactions can be so fraught. No one has to do anything for you, so it's really lovely that anyone chooses to help at all.

Maybe I’m a hypocrite, but maybe that’s enough for now.

Wow this is so beautiful!

Just everything about this whole post. Yea to the shared despair and sadness. Yes to the shared disappointment that we just don’t do better. And yes to all things dogs and hope.